650 Enchanted and Mystical Sites Across Britain

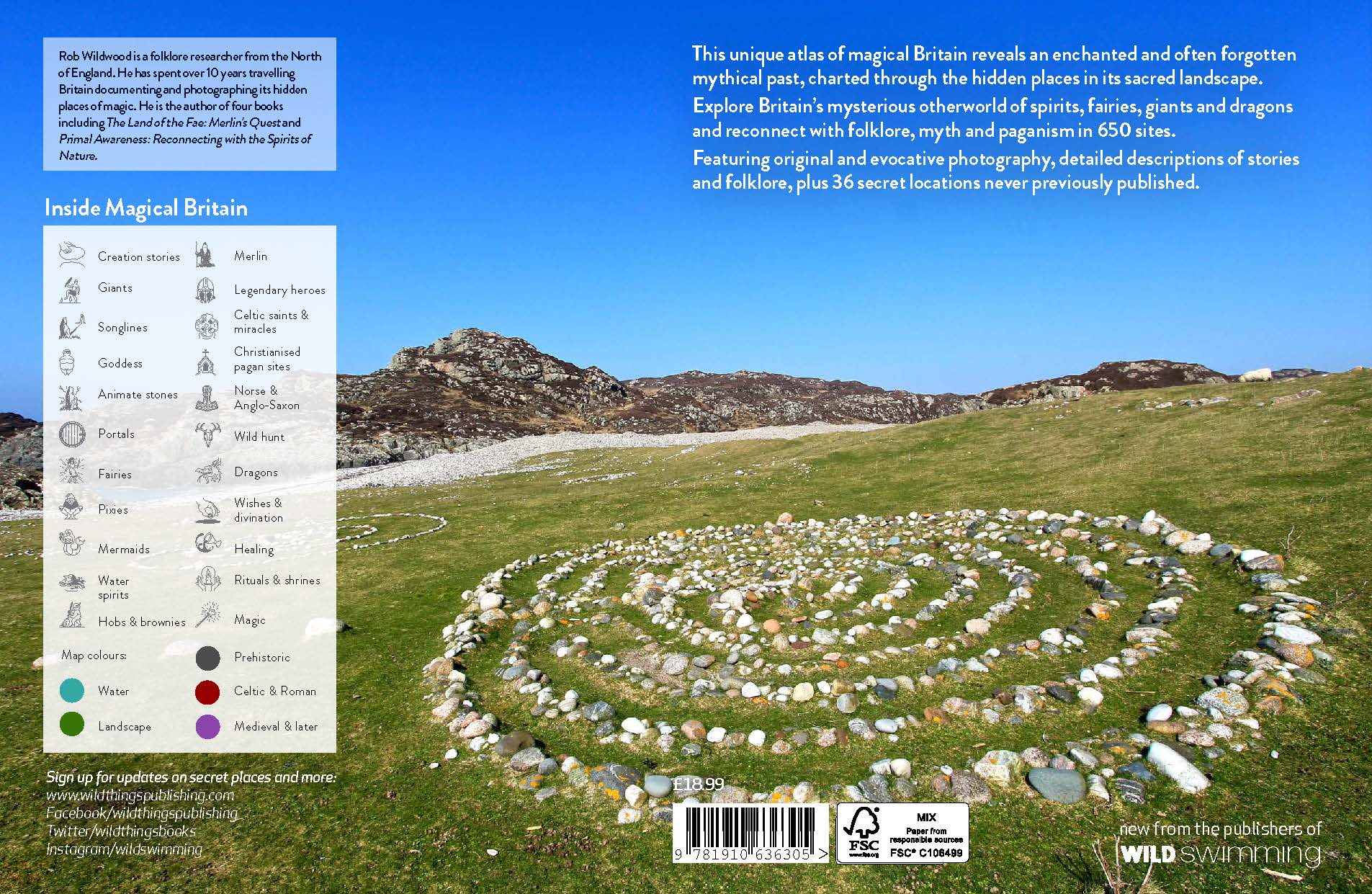

This unique atlas of magical Britain reveals an enchanted and often forgotten mythical past, charted through the hidden places in its sacred landscape. Explore Britain’s mysterious otherworld of spirits, fairies, giants and dragons and reconnect with folklore, myth and paganism in 650 sites. Featuring original and evocative photography, detailed descriptions of stories and folklore, plus 36 secret locations never previously published.

Rob Wildwood is a folklore researcher from the North of England. He has spent over 10 years travelling Britain documenting and photographing its hidden places of magic. He is the author of four books including The Land of the Fae: Merlin's Quest and Primal Awareness: Reconnecting with the Spirits of Nature.

This unique atlas of magical Britain reveals an enchanted and often forgotten mythical past, charted through the hidden places in its sacred landscape.

Explore Britain’s mysterious otherworld of spirits, fairies, giants and dragons and reconnect with folklore, myth and paganism in 650 sites.

Featuring original and evocative photography, detailed descriptions of stories and folklore, plus 36 secret locations never previously published.

- Journey to the hidden places in our sacred landscape. Discover Britain’s forgotten magical past and mythical sites:

- Places featured in the stories of King Arthur, Merlin and the Celtic Saints

- Entrances to the Otherworld

- Spirits in the stone, creation stories and giants’ strongholds

- Sites of healing, divination and wish-making

- Secret shrines and places of ancient ritual

- Sacred Goddess sites in the landscape

- Legendary locations of Norse mythology

- Dragons and Mermaids

About the author

Rob Wildwood is a folklore researcher from the North of England. He has spent over 10 years travelling Britain documenting and photographing its hidden places of magic. He is the author of four books including The Land of the Fae: Merlin’s Quest and Primal Awareness: Reconnecting with the Spirits of Nature.

Table of Contents

Regional overview 6

Britain’s magical history 9

How to use this book 14

Visiting a magical place 15

The Celtic wheel of the year 16

Creation 18

Giants 20

Songlines – Britain’s mythic routes 22

Mother goddess 24

Animate stones 26

Portals – entrances to the Otherworld 28

Fairies 30

Pixies & piskies 32

Mermaids & other ocean spirits 34

Water spirits of rivers, lakes & springs 36

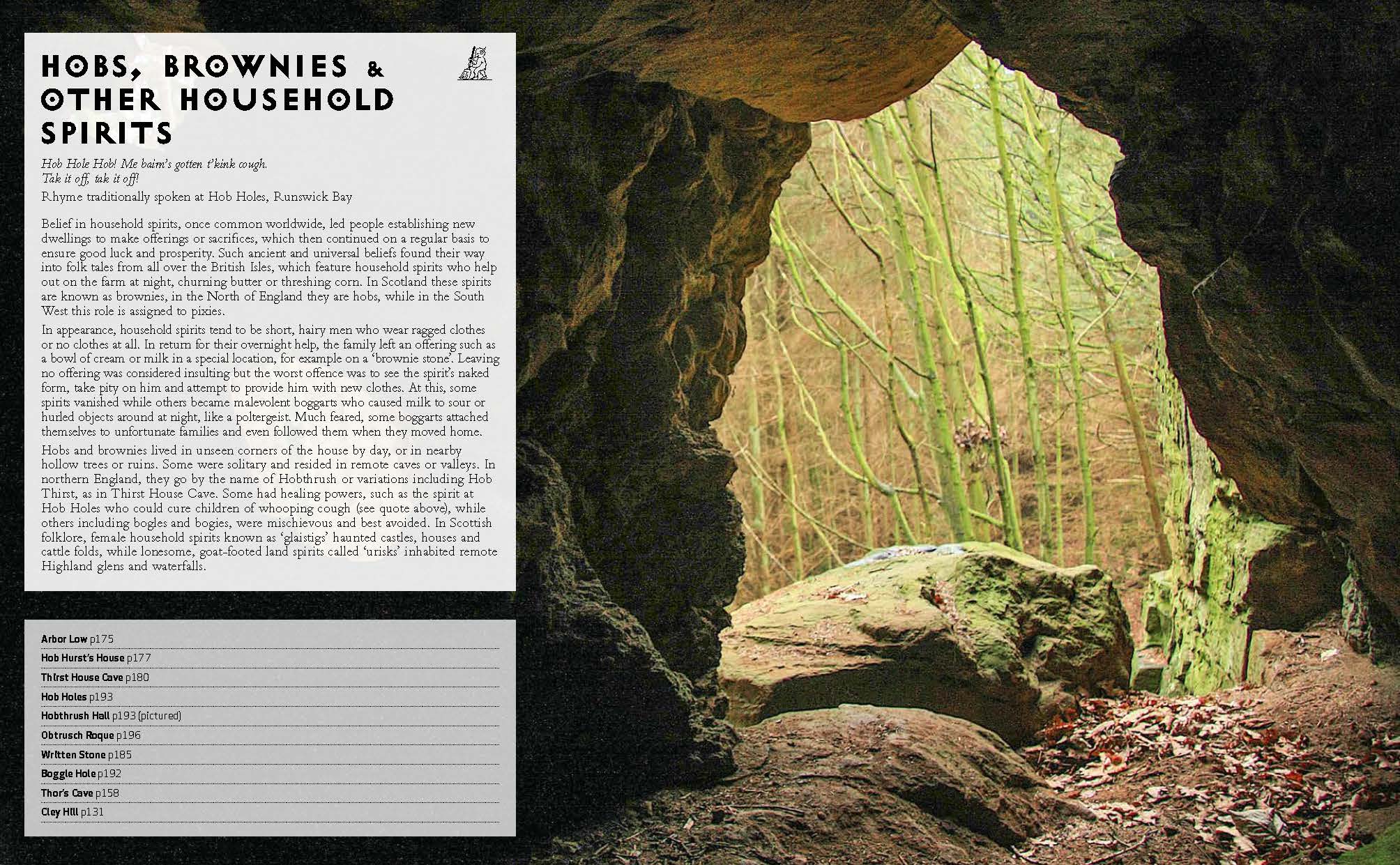

Hobs, brownies & other household spirits 38

Merlin 40

Arthur and other legendary heroes 42

Celtic saints & miracles 44

Christianised pagan sites 46

Norse & Anglo-Saxon mythology 48

The Wild Hunt & otherworldly hounds 50

Dragons 52

Wishes & divination 54

Places of healing 56

Rituals & shrines 58

Magic 60

REGIONAL CHAPTERS 62

Placename index 330

Places by category 332

Landscape glossary 335

Acknowledgements & further reading 336

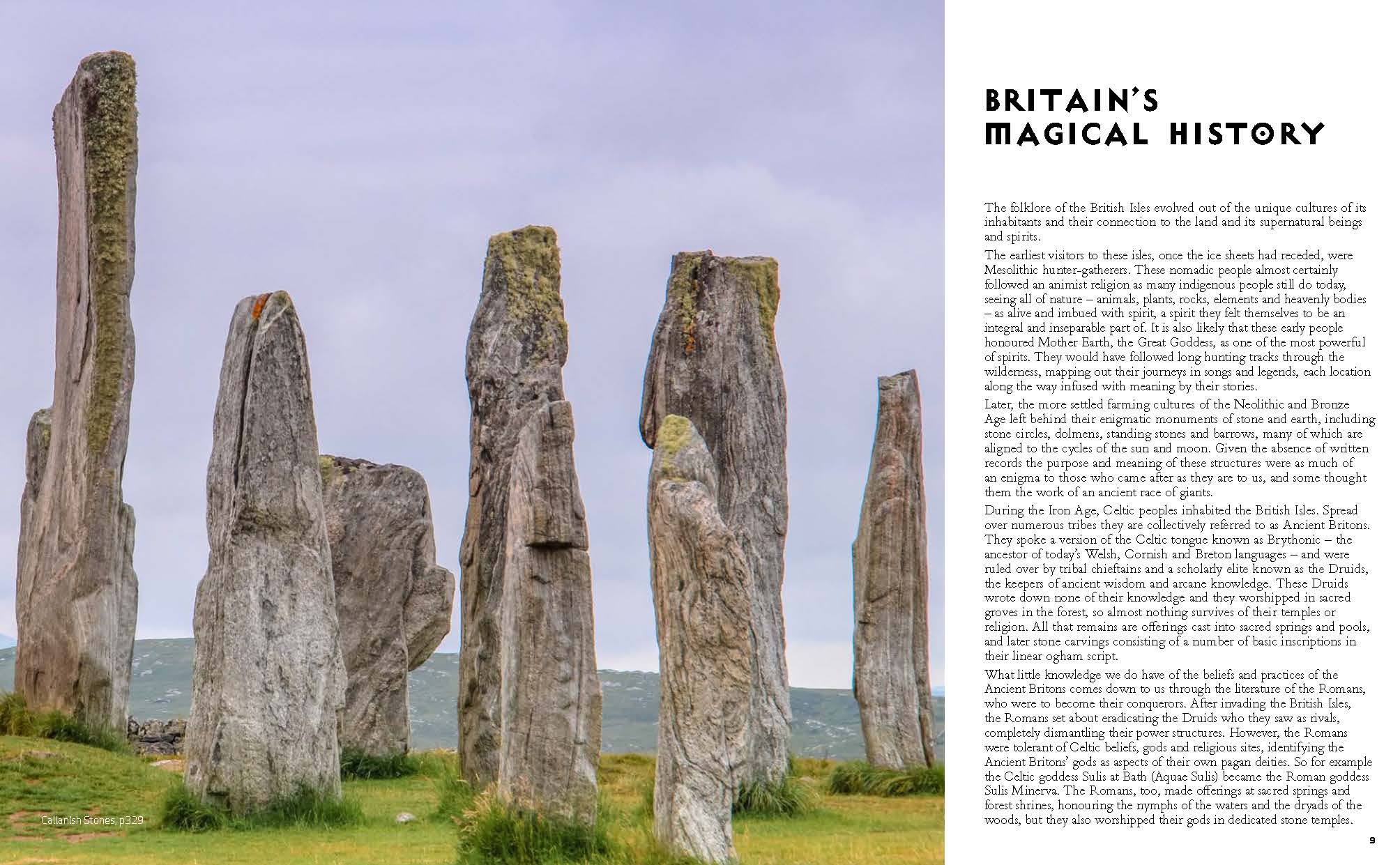

Britain’s Magical History

The folklore of the British Isles evolved out of the unique cultures of its inhabitants and their connection to the land and its supernatural beings and spirits. The earliest visitors to these isles, once the ice sheets had receded, were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. These nomadic people almost certainly followed an animist religion as many indigenous people still do today, seeing all of nature – animals, plants, rocks, elements and heavenly bodies – as alive and imbued with spirit, a spirit they felt themselves to be an integral and inseparable part of. It is also likely that these early people honoured Mother Earth, the Great Goddess, as one of the most powerful of spirits. They would have followed long hunting tracks through the wilderness, mapping out their journeys in songs and legends, each location along the way infused with meaning by their stories.

Later, the more settled farming cultures of the Neolithic and Bronze Age left behind their enigmatic monuments of stone and earth, including stone circles, dolmens, standing stones and barrows, many of which are aligned to the cycles of the sun and moon. Given the absence of written records the purpose and meaning of these structures were as much of an enigma to those who came after as they are to us, and some thought them the work of an ancient race of giants.

During the Iron Age, Celtic peoples inhabited the British Isles. Spread over numerous tribes they are collectively referred to as Ancient Britons. They spoke a version of the Celtic tongue known as Brythonic – the ancestor of today’s Welsh, Cornish and Breton languages – and were ruled over by tribal chieftains and a scholarly elite known as the Druids, the keepers of ancient wisdom and arcane knowledge. These Druids wrote down none of their knowledge and they worshipped in sacred groves in the forest, so almost nothing survives of their temples or religion. All that remains are offerings cast into sacred springs and pools, and later stone carvings consisting of a number of basic inscriptions in their linear ogham script.

What little knowledge we do have of the beliefs and practices of the Ancient Britons comes down to us through the literature of the Romans, who were to become their conquerors. After invading the British Isles, the Romans set about eradicating the Druids who they saw as rivals, completely dismantling their power structures. However, the Romans were tolerant of Celtic beliefs, gods and religious sites, identifying the Ancient Britons’ gods as aspects of their own pagan deities. So for example the Celtic goddess Sulis at Bath (Aquae Sulis) became the Roman goddess Sulis Minerva. The Romans, too, made offerings at sacred springs and forest shrines, honouring the nymphs of the waters and the dryads of the woods, but they also worshipped their gods in dedicated stone temples.

During the Roman occupation of Britain, which lasted almost 400 years, Christianity arrived in the British Isles, and by the early medieval period it had evolved into a unique form known as ‘Celtic Christianity’. Yet after the Romans departed, Britain was plunged into a ‘Dark Age’ as government structures collapsed, Roman towns and fortifications were abandoned, and the written historical record came to an end. Out of this darkness emerged some of Britain’s most colourful and enduring myths – tales of King Arthur and his knights, the wizard Merlin and the Welsh bard Taliesin.

The Romano-British Celts, Romanised successors to the Ancient Britons, were at this time being assailed from all sides. From the east came the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, later to be referred to collectively as the Anglo-Saxons. The Scots-Gaels from Ireland advanced from the west and from the north came the Picts –these two would later amalgamate to become the Scottish Highlanders. A desperate rearguard action was being fought by the new Romano-British kingdoms against these savage invaders. Warlords like Arthur would achieve some victories and stem the tide for a while, but their fate was sealed and the Anglo-Saxons would eventually overrun the whole of the land that would become known as England. Only in Wales and Cornwall did the Ancient Britons endure and they also held onto the Lowlands of Scotland for some time until these were finally relinquished, going down in Welsh legend as the lost lands of the ‘Hen Ogledd’ the Old North.

It is these Brythonic Celtic peoples who retained the original lore of the land of Britain and so were keepers of its ancient wisdom and folk knowledge. The Anglo-Saxon newcomers had less of a relationship with this new land and so imprinted upon it far fewer stories and legends than their Celtic neighbours. This is one of the reasons why there is such a dearth of folklore in the southeast of the country compared to the riches of the Celtic west. The flatter, more arable landscape in the east, its closer ties to the continent and its earlier modernisation are also likely to be contributory factors.

Cornwall is renowned for its wealth of unique folklore about giants, piskies, spriggans and knockers, for its abundance of holy wells and prehistoric sites, and for the birthplace of King Arthur at Tintagel. Wales, too, has its own fairy folk, the Tylwyth Teg and the shining beings known as Ellyllon. It is also the home of Myrddin Emrys (the Welsh Merlin), and produced an abundance of Celtic saints – itinerant priests who travelled through Britain establishing hermitages and performing miraculous acts.

In the Old North, the Brythonic speaking Britons carried their own versions of the Merlin and Arthur stories. They occupied the land between the two Roman walls (Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall), but were eventually defeated by the incoming Angles and so Lowland Scotland became ‘Anglicised’. Their mythology became linked to that of the Anglo-Saxons and they retained Anglo-Saxon terms such as the word elf, found in Scots phrases such as elfhame.

The Scots-Gaels in the Highlands of Scotland had very different mythology and folklore to the Lowland Scots further south. These Gaelic speaking Celts had no tales about King Arthur or Merlin, instead their heroes were Fingal (Fionn mac Cumhaill) and the warrior-poet Ossian, and their fairy folk were known as the sith (sidhe) who lived in fairy hills called sitheans. They also had a whole host of other supernatural beings unique to the Highlands, such as the glaistig, the urisk and the each-uisge (water horse). Of the ancient Picts, the original Brythonic inhabitants of Highland Scotland, we know almost nothing as they left no written record. Only their enigmatic carved, picture-stones remain, hinting at a lost mythology and belief system.

During the period referred to as the Dark Ages, Christianity and the old Romano-Celtic paganism existed side by side in a patchwork of small kingdoms, some following the new religion and some the old. Pagan figures such as Myrddin Wylt (the Scottish Merlin) interacted with Christians including St Kentigern, and legendary saints St Columba and St Aidan established missions on the holy islands of Iona and Lindisfarne. Celtic Christianity would eventually win the hearts and minds of the remaining Celtic peoples as paganism slowly faded back into the mists of time.

During this period the Anglo-Saxons remained firmly wedded to their old gods: Woden, Thunor and Frigga. But over time they too would ultimately succumb to the new religion, as Celtic Christian missions spread south from Lindisfarne and Roman Catholic missions spread north from Kent. These two versions of Christianity disagreed on many points of Christian theology and practice however, and so the inevitable confrontation came to a head in 664 at the Synod of Whitby. Roman Christianity won the day and so Celtic Christianity and the age of the magical Celtic saints would eventually fade into memory. Yet with the approval of the Roman Catholic Church veneration of the old Celtic saints would continue, especially in Cornwall and Wales. Right up to the present day the numerous holy wells and shrines dedicated to them are still believed to have miraculous healing powers. The old pagan ways were not entirely forgotten either. Many pagan shrines became Christian churches, sacred springs became holy wells, the fairies and the elves were still believed to inhabit the mounds, and people’s lives were filled with magic and ritual. Yet Britain was now a largely Christian land, with close ties to the Church of Rome.

The triumph of Christianity was to be short-lived, however, as from the end of the 8th century the heathen Norsemen, known later as Vikings, started to ravage these shores. Coming first as raiders, then invaders and finally as settlers, they still followed their old gods Odin, Thor and Freya. They worshipped in sacred groves and wooden temples where they sometimes made blood sacrifices. Their religion was very similar to that of the Anglo-Saxons who had arrived centuries before them and they worshipped a similar pantheon of gods, albeit with slightly different names.

The Norse, and then the Danish Vikings, very nearly succeeded in conquering the whole of England until they were eventually defeated by the Saxon kings of Wessex. The subsequent treaty still gave the Vikings control of more than half of the country, roughly north of the line of the rivers Thames and Severn. This is why many towns, villages and landscape features in the north of England still have Viking names and a unique character distinct from those in the South. The Vikings were the last pagan peoples to invade Britain and they left the names of their pagan gods imprinted upon the landscape, but within a generation or two of settling this land the Vikings too would be converted to Christianity, merging with the English to become the Anglo-Danes. It is not known when, or even if, paganism eventually died out, but we do know that many centuries later kings were still issuing edicts banning many specific details of pagan practice – evidence that it was indeed still being practised!

The Vikings also settled around the coasts of Scotland, particularly in the far north where they established ‘The Kingdom of the Isles’. Orkney still retains its Viking heritage and its own unique folklore about trows, finfolk and dwarves. Other attempts were made by Viking kings to conquer the British Isles but the ultimately successful invasion came not from Scandinavia but from the south. These were the Normans, former Vikings themselves who had settled in Northern France and adopted French customs and language. They brought with them many French ideas, including the introduction of the French word fée (fairy) into the English language, which largely displaced the Old English concept of elves.

Allied to the Norman French were the Bretons, descendants of Brythonic-speaking Celts who had fled the British Isles for Northern France during the ‘Dark Ages’, taking their Celtic heritage with them. It was the influence of these Bretons that probably led to a renewed interest in British (Celtic as opposed to English) history, culminating in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s epic History of the Kings of Britain, appearing in 1136. He covered the whole of British history, starting with the battles between men and giants when people first arrived on these shores; but he is mainly remembered for writing extensively about the exploits of King Arthur and Merlin. His hugely successful book prompted more authors from France and Germany to write their own versions of the Arthurian romances, and so began the whole genre of Arthurian myth that is still popular today.

From the medieval period we also have the chronicles of such notables as Gerald of Wales, Gervase of Tilbury, Ralph of Coggeshall and Walter Map whose writings are filled with supernatural tales and observances, as well as Britain’s first recorded fairy tales. William Shakespeare would later draw extensively on these medieval tales from Britain’s semi-legendary past. It was also during this period that many ancient Welsh bardic tales were finally committed to paper, tales that would later be compiled into a celebrated collection, the Mabinogion. They tell of Welsh heroes, journeys to the Otherworld, magical cauldrons, perilous quests and the exploits of Arthur and his band of warriors, all set in a mythical Welsh past.

During the Protestant reformation, old Roman Catholic ’superstitions’ such as the veneration of saint’s relics and rituals at shrines and holy wells were actively banned. Many ancient traditions, which had been given a thin veneer of Christian acceptability under Roman Catholicism, were lost, culminating in the fundamentalist Puritan movement of the 17th century when ancient monuments, sacred sites and anything ‘popish’ were actively being destroyed. Fortunately, antiquarians such as William Stukeley, John Aubrey and William Camden were recording local folklore, customs and details about ancient monuments which would otherwise have been lost. William Stukeley, however, was also mainly responsible for the unfounded belief that stone circles and other prehistoric sites were places of Druid worship. It was also during this time that witches were persecuted, making people terrified to have any connection with magic or ancient superstitions. Fairies and other supernatural beings were cast as demons and those who consulted them were seen as consorting with the Devil himself. During this period, it is likely that many folk tales involving the old gods, giants or fairies were recast as the exploits of devils, demons and imps.

One of the most influential, and fanciful, of antiquarians was Sir Walter Scott, who at the beginning of the 19th century published his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, which popularised such enduring tales as Tam-Lin and Thomas the Rhymer, describing their journeys into Elfland. The antiquarian movement continued into the Victorian period and beyond when folklore and customs from almost every part of the country were being recorded in detail. These records were to prove invaluable as most traditions would soon die out with the coming of industrialisation, surviving only in the remote western and upland regions of the country. The Victorians, however, were responsible for the twee depictions of fairies with wings.

In the early 20th century, many traditional storytellers, particularly in Wales, Cornwall and the Highlands and islands of Scotland, preserved the old tales and folklore spoken in the original Celtic languages. But with the coming of radio and then television, storytelling as a form of entertainment rapidly died out and many of the tales not written down have been lost to us.

Today most people have largely forgotten their ancient connection to the land and its stories, seeming to prefer a sanitised version of fairy tales that are no longer rooted in the landscape and its web of supernatural beings and spirits. Myths and legends are more than just stories; they are a way for us to remember our magical relationship with the land. It is through restorying the landscape that we may one day regain this ancient respect and reverence for the land. Indigenous people know what we perhaps no longer remember: that only through respecting its sacredness will the land endure and sustain us for centuries to come.

For more pictures and information about magical places please 'like' the Magical Places Facebook Page